Right, today's post will be relating to revenue and more specifically a firms revenue. We'll start with a few of the basic bits of terminology that I'll be using throughout this post. Firstly, total revenue. This is fairly self-explanatory but I'll give a definition anyway. Total revenue is a firms total earnings in a period of time from the sale of a particular amount of goods, the formula is better known as price x quantity. Average revenue next and this is the amount a firm earns for each unit sold, the formula for this is (total revenue) / (quantity) which you may have noticed just equals price. Marginal revenue is the final term, this refers to the extra revenue gained from selling one more unit of a good. The formula for marginal revenue is (change in total revenue) / (change in quantity).

We'll first look at the revenue curves for a small firm. We'll be assuming this firm is in a perfectly competitive market (Will do a blog post on this later today/tomorrow). Basically, this means that the firms are generally too small to have any effect on the price of the good they are selling. If they raise their price no-one will buy from them, if they lower their price they will find an overwhelming demand and probably be charging less than the cost to produce the good. That being said, the market forces determine the price the firm has to charge.

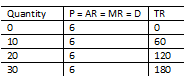

As you can see here, the demand and supply have met in the market and this has created a price for the good. The firm, shown on the left has a demand curve of this price because consumers will only buy from the firm at this price. No matter the quantity, the price will remain the same. Another note on this, D = AR = MR because the price is constant. The average revenue and marginal revenue will always be the same because we are working with a constant price. We can model the total revenue of a firm as well. This is simple, first we create a table with the quantity supplied, price and total revenue. We then plot this table. Simple.

Simple as that for a total revenue curve for a small firm. However, when it comes to larger firms and the price of the good does vary with output we are struck with a different scenario. The average revenue curve is still equal to the price and will be the demand curve, but this time it will be downward sloping as with the normal characteristic of demand. The marginal revenue curve will also be downward sloping, but at a faster rate than the average revenue curve and will more than likely reach negative values. This is due to the diminishing marginal rate of production, the marginal revenue falls with each additional good you produce up to a point where producing another good will generate no additional revenue and may even decrease revenue. Before the quantity where marginal revenue equals zero, the average revenue is elastic because an increase in quantity will lead to a rise in revenue. After this point, it's inelastic because a rise in quantity leads to a fall in total revenue.

And all that's left to add to this is the shape of the total revenue curve when the price varies with output. I should note, this happens in larger firms when they can effect the market price. The total revenue curve would be somewhat hill shaped. It would slope up, reach a peak at some unknown point and then slop down again afterwards. You may be thinking "Ok, great... Why?"! Well, this will come in useful in the next posts when we look at profit maximisation of a firm.

Thank you for reading again, keep watching for the next few posts which will relate and link to this one. Have a good day!

Sam.

Sam.